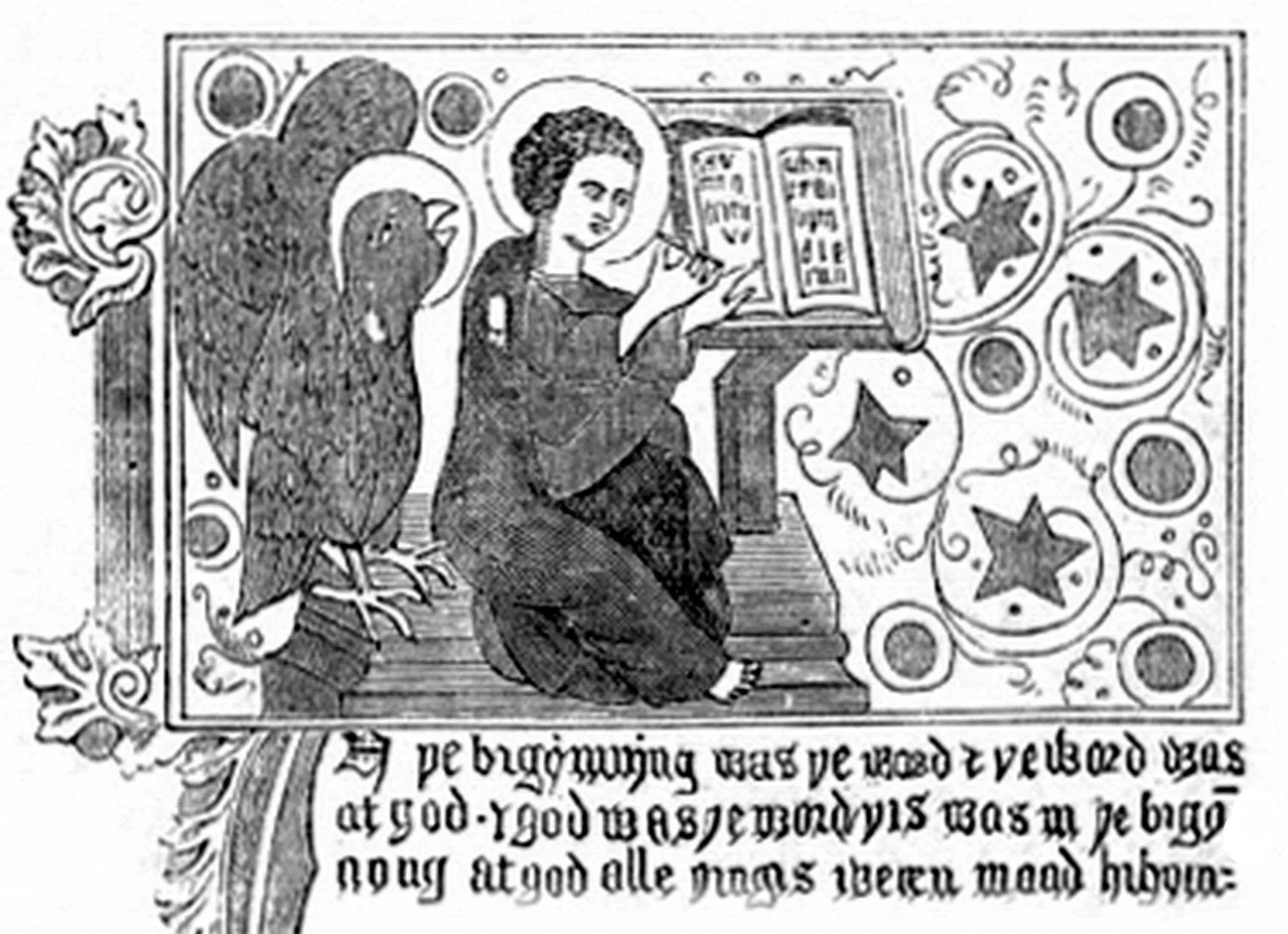

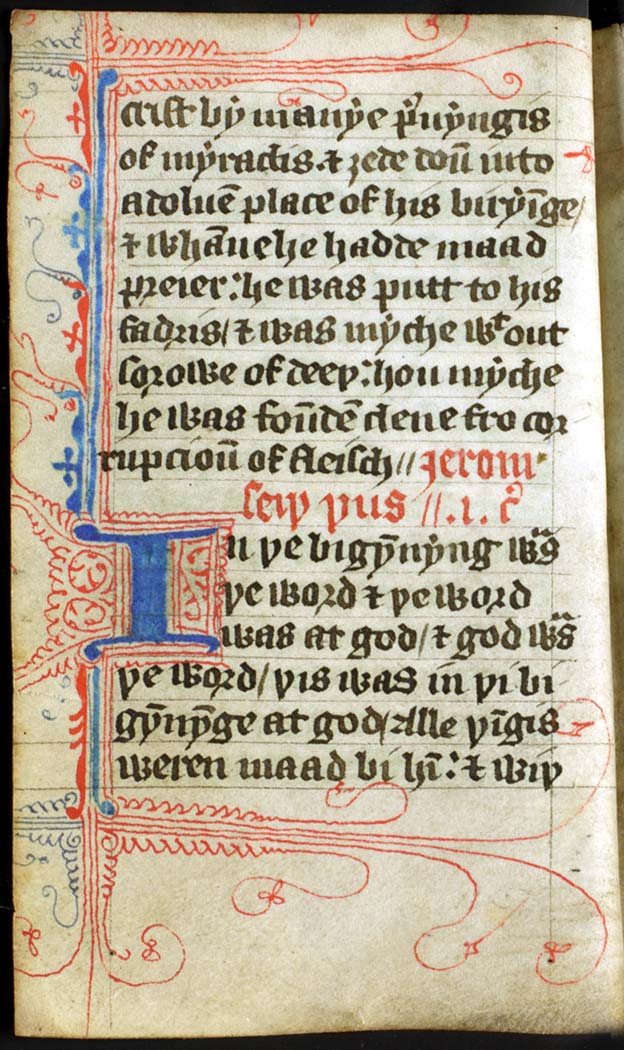

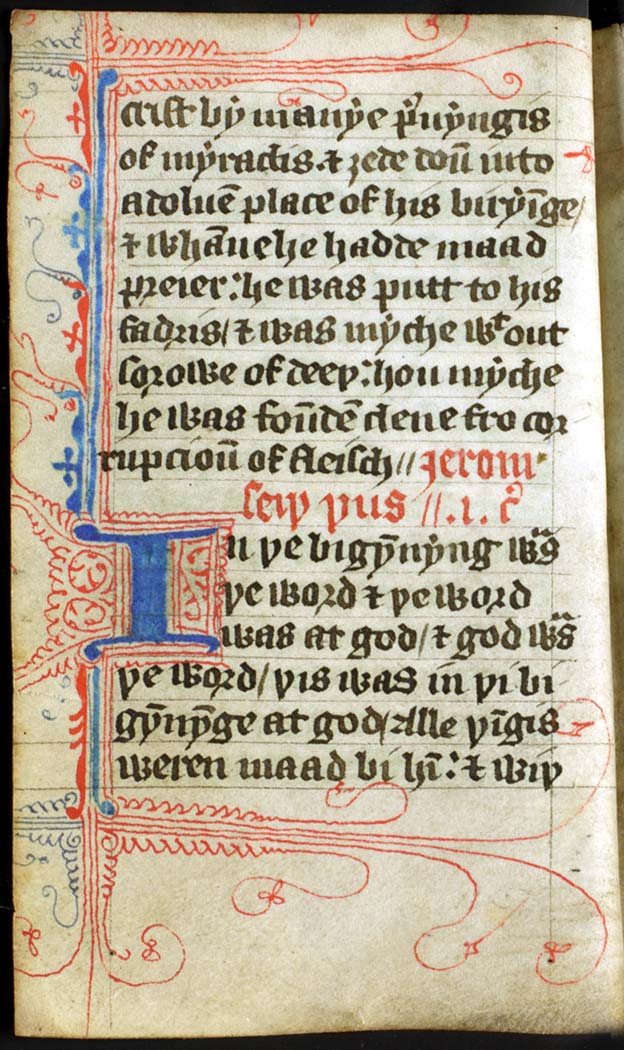

John’s Gospel in a copy of John Wycliffe's translation of the Bible

John’s Gospel in a copy of John Wycliffe's translation of the Bible

At the right time, God had the right people ready and able

After the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt, Wycliffe’s position at the heart of English life became untenable. He was obliged to retire to Lutterworth where he had the freedom to translate the Latin Scriptures into the language of the common people. We know little of how he did that, but almost certainly he had help from his followers. At the right time, God had the right people ready and able.

In the years after his death in 1384, it was his followers, the Lollards, who went around teaching from handwritten copies of the translation. What a Bible impact team!

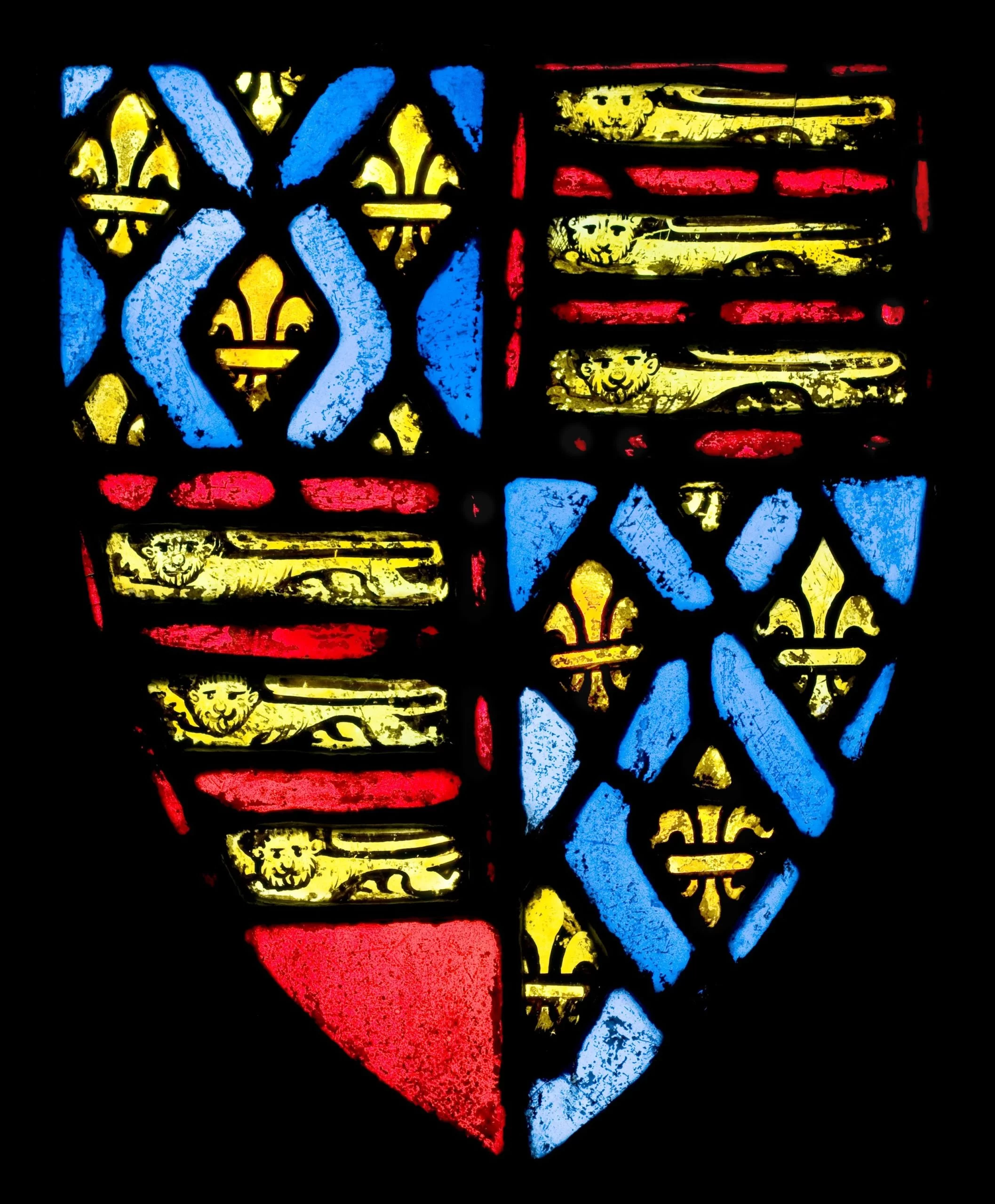

Despite severe persecution, the Lollards continued to make an impact; in the end it was their vision that prevailed. The Church tried to suppress Wycliffe’s influence, but the fact that he showed translation could – indeed should – be done, sent shock waves around Europe that no church council could stop. Jan Hus in Prague was deeply influenced by Wycliffe’s thinking and from Hus there is a clear link to the 16th-century Reformation.

And the Bible translation movement continues today, the effects of which ripple out into all areas of life and from generation to generation. Follow the link below to find out more.