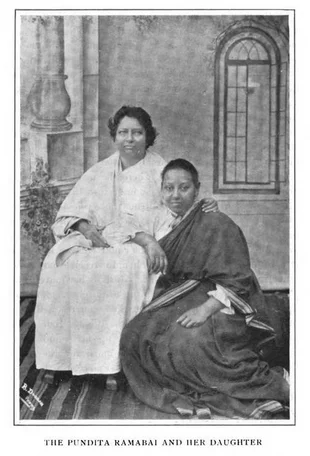

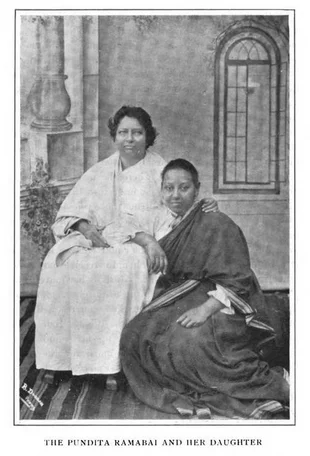

Pandita Ramabai and her daughter, Manorama Bai, in a 1911 publication

Pandita Ramabai and her daughter, Manorama Bai, in a 1911 publication

The worst position

In 1880 her brother also died. Alone in the world, she married a friend of her brother. But in doing so, she was held to have polluted herself, for he was from the lower Shudra caste. They had a daughter, and then her husband died too. So Ramabai was left in the worst of all positions in the India of that time: an orphan, a widow and a single mother.

The longing for social reform that would improve the lot of women in areas such as child marriage and literacy and education grew ever stronger in Ramabai. She learnt English, started to write, and met, among others, theologian Nehemiah Goreh, who helped her to an understanding of the Christian faith.

In 1883, Pandita Ramabai travelled to England for her studies and was invited to stay at an Anglican community. In the community’s London Rescue Home, she saw first-hand how women who had fallen on hard times were helped. This experience moved her enormously. In particular, the story of the Samaritan woman in John 4 impacted her. Acknowledging that ‘Christ was truly the divine Saviour’, she was baptised. And yet she wrote later, that ‘though she had found the Christian religion, she had not found Christ.’