Note: This article includes quotes of racist comments. Wycliffe Bible Translators condemns this language, and the practices that went with it. We include them here in order to portray with integrity some of what Samuel Ajayi Crowther experienced and how he overcame great obstacles, and to celebrate the wonderful things God accomplished through him.

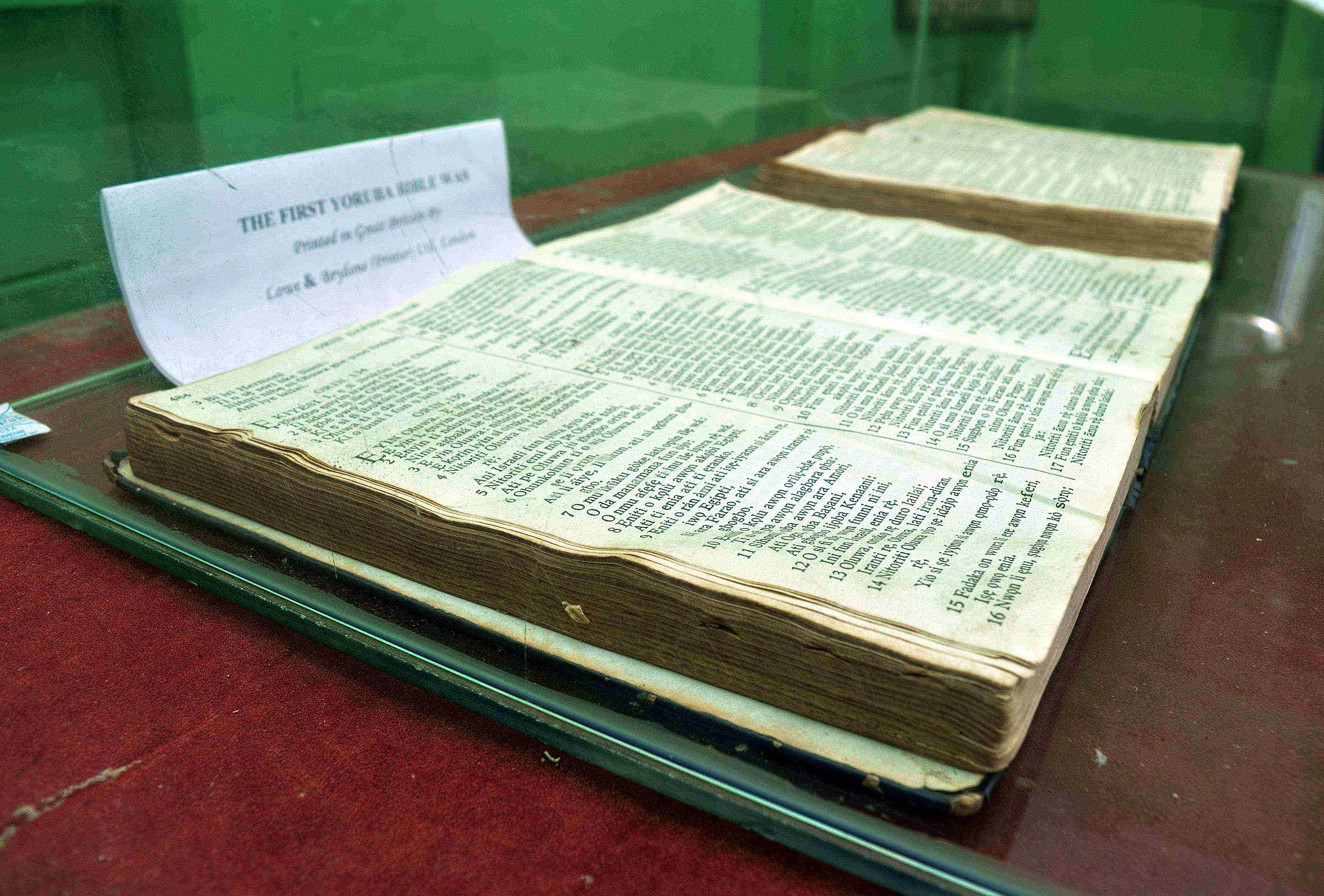

‘…the “Sword of the Spirit” [the Bible], placed in the hands of the congregations, in their own tongue, will do more… than all our preaching, teaching and meetings of so many years put together’ – Samuel Ajayi Crowther

The Right Reverend Dr Samuel Ajayi Crowther was the first African bishop in the Anglican Church and the first African Bible translator of the modern era.

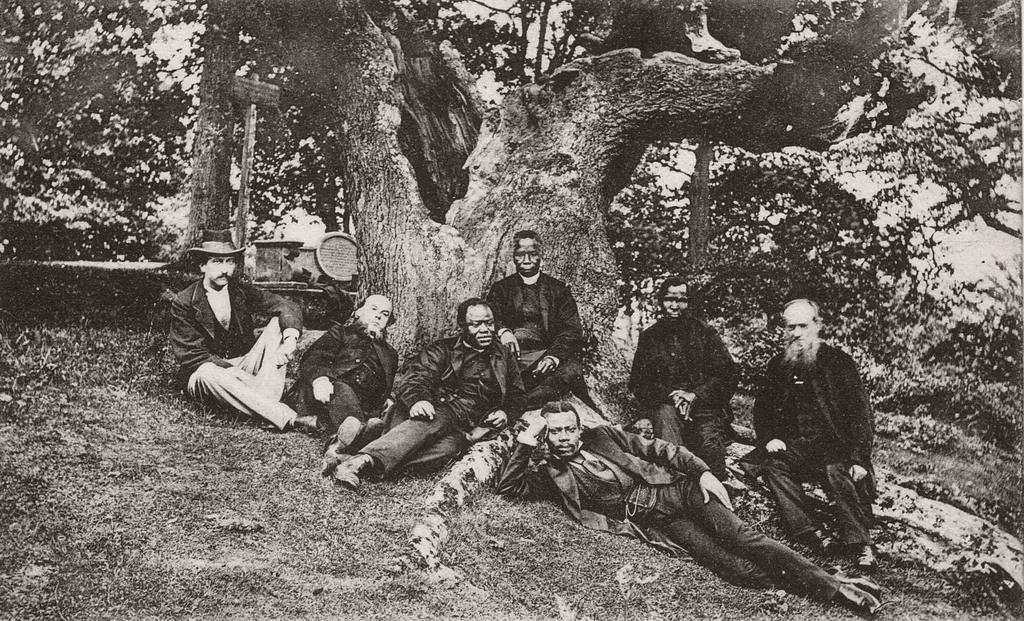

In 1889, the 80-year-old Crowther celebrated 25 years as bishop. Yet just a few years later, when the World Missionary Conference opened in 1910, there was not one African amongst all the missionaries gathered in Edinburgh. Plans were drawn up to ‘carry the Gospel to all the non-Christian world’, but those plans apparently did not acknowledge that in most areas of church growth on the African continent, the vast majority of missionaries were black. For example, in 1906, the Church Mission Society (CMS) had 8,850 missionaries known at the time as ‘native agents’ compared to 975 ‘European missionaries’.1

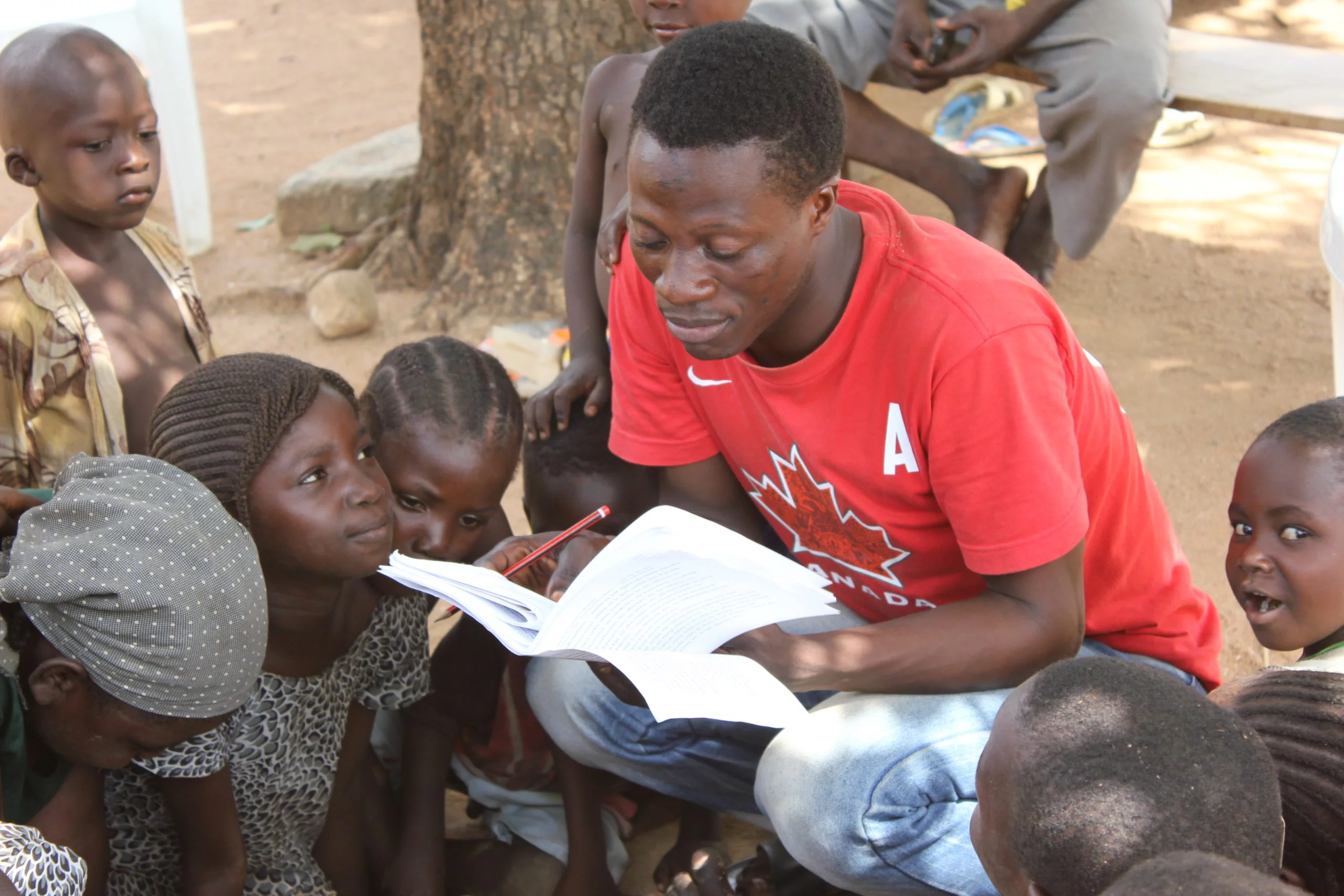

Widely known as a gentle, modest man, Crowther was responsible for successfully opening up the Niger to the gospel as a missionary bishop for CMS. He employed a compelling dialogue approach, using local languages and the Scriptures. Indeed, he translated the entire Bible into Yoruba (spoken mainly in West Africa, including Crowther’s home in what is now Nigeria). Yoruba was, after all, his mother tongue.

Ahead of his time

These facts alone deserve celebration. His Bible translation was also remarkably effective, and his approach to the study and practice of mission was way ahead of its time – even more cause for re-appraising his extraordinary life.

At the age of 12, Ajayi (who hadn’t yet taken the name Samuel Crowther) was captured by Fulani slave traders from his home town of Osugun in what is now Oyo State, Nigeria. He ended up in the Lagos slave market, where he was sold to Portuguese traders who put him on a ship.

This ship was then attacked by a British anti-slavery warship. Of the 189 enslaved people on board, 102 died in the attempt to rescue them, but Ajayi survived and was taken by the British navy to Freetown, Sierra Leone. Here he was placed in a CMS school, where he learnt English and was taught the Scriptures. Along with many others, he decided to follow Christ and, in 1825, was baptised. At that time it was common to take a new name at baptism. Indeed, missionaries were known to insist on it.2 It was at this point that Ajayi took the name Samuel Crowther after a CMS pioneer.