Go back 500 years, and the only Scripture that was legally available in England was the Latin Vulgate. Genesis chapter 1 opened as follows:

In principio creavit Deus caelum et terram. Terra autem erat inanis et vacua et tenebrae errant super faciem abyssi, et spiritus Dei ferebatur super aquas. Dixitque Deus: Fiat lux. Et facta est lux.

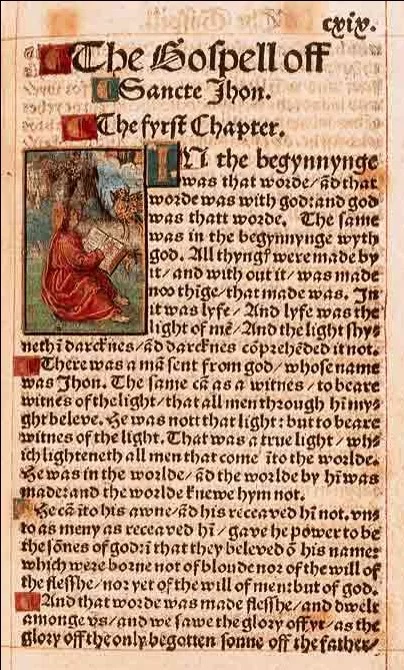

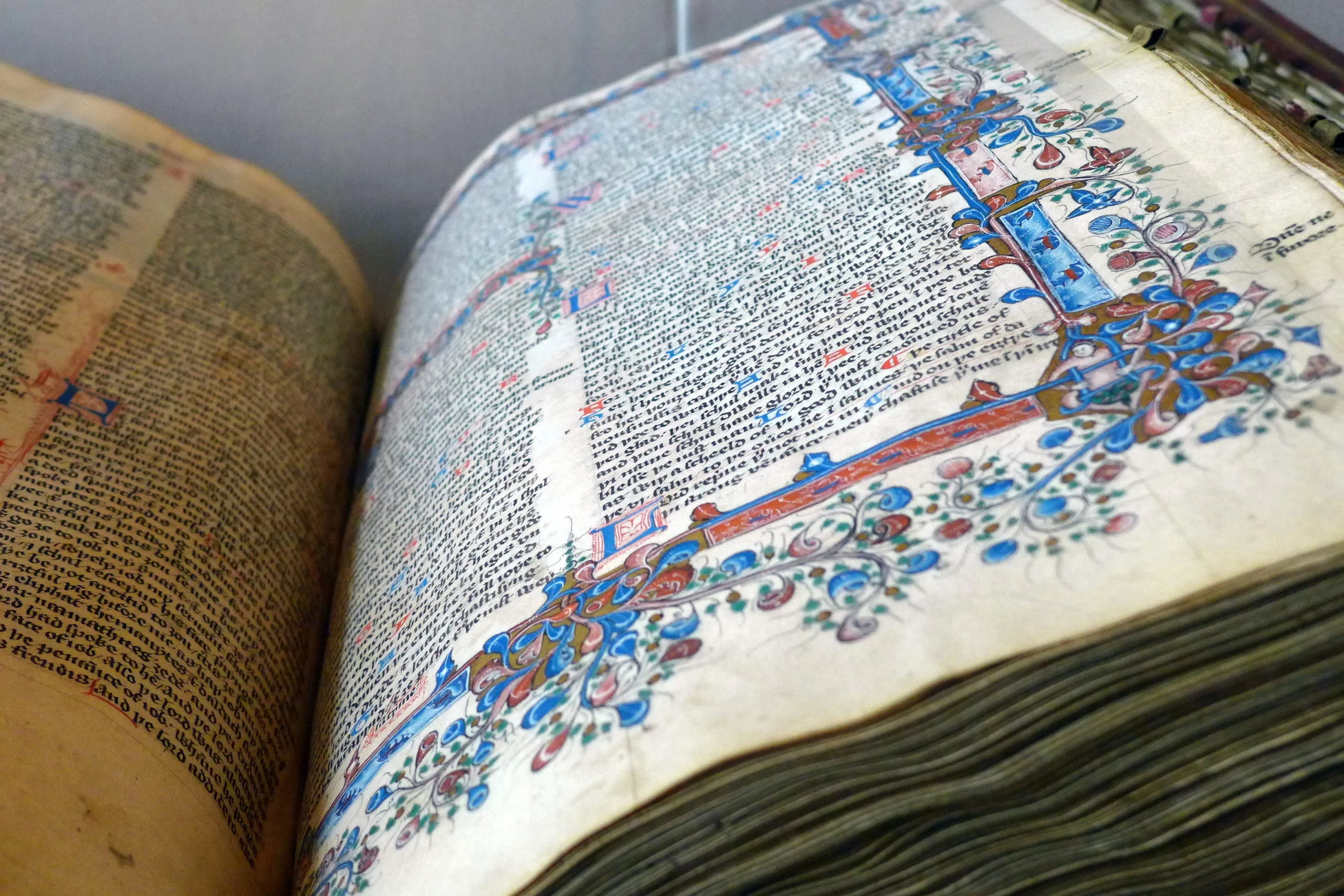

If you moved in certain circles, you may also have had access to John Wycliffe’s outlawed, handwritten Bible of 1382, which translated this Latin:

In the beginning God made of nought heaven and earth. Forsooth the earth was idle and void, and darknesses were on the face of depth: and the Spirit of the Lord was born on the waters. And God said, Light be made and light was made.